Wonderful, crazy wild blog from Delhi – with great good humour and energy.

Turkish tea II

George Orwell’s cup of tea

George Orwell, the great English satirist and political essayist, author of 1984 and Animal Farm, wrote this short essay in the Evening Standard. It defines his ideal of ‘a nice cup of tea.’

I’m very grateful to Alexandra Hoover for bringing it back to my attention in her lovely blog at

http://www.tching.com/2011/01/some-tips-on-tea-from-george-orwells-essay-a-nice-cup-of-tea/

A Nice Cup of Tea

By George Orwell

Evening Standard, 12 January 1946.

If you look up ‘tea’ in the first cookery book that comes to hand you will probably find that it is unmentioned; or at most you will find a few lines of sketchy instructions which give no ruling on several of the most important points.

This is curious, not only because tea is one of the main stays of civilization in this country, as well as in Eire, Australia and New Zealand, but because the best manner of making it is the subject of violent disputes.

When I look through my own recipe for the perfect cup of tea, I find no fewer than eleven outstanding points. On perhaps two of them there would be pretty general agreement, but at least four others are acutely controversial. Here are my own eleven rules, every one of which I regard as golden:

First of all, one should use Indian or Ceylonese tea. China tea has virtues which are not to be despised nowadays — it is economical, and one can drink it without milk — but there is not much stimulation in it. One does not feel wiser, braver or more optimistic after drinking it. Anyone who has used that comforting phrase ‘a nice cup of tea’ invariably means Indian tea.

Secondly, tea should be made in small quantities — that is, in a teapot. Tea out of an urn is always tasteless, while army tea, made in a cauldron, tastes of grease and whitewash. The teapot should be made of china or earthenware. Silver or Britanniaware teapots produce inferior tea and enamel pots are worse; though curiously enough a pewter teapot (a rarity nowadays) is not so bad.

Thirdly, the pot should be warmed beforehand. This is better done by placing it on the hob than by the usual method of swilling it out with hot water.

Fourthly, the tea should be strong. For a pot holding a quart, if you are going to fill it nearly to the brim, six heaped teaspoons would be about right. In a time of rationing, this is not an idea that can be realized on every day of the week, but I maintain that one strong cup of tea is better than twenty weak ones. All true tea lovers not only like their tea strong, but like it a little stronger with each year that passes — a fact which is recognized in the extra ration issued to old-age pensioners.

Fifthly, the tea should be put straight into the pot. No strainers, muslin bags or other devices to imprison the tea. In some countries teapots are fitted with little dangling baskets under the spout to catch the stray leaves, which are supposed to be harmful. Actually one can swallow tea-leaves in considerable quantities without ill effect, and if the tea is not loose in the pot it never infuses properly.

Sixthly, one should take the teapot to the kettle and not the other way about. The water should be actually boiling at the moment of impact, which means that one should keep it on the flame while one pours. Some people add that one should only use water that has been freshly brought to the boil, but I have never noticed that it makes any difference.

Seventhly, after making the tea, one should stir it, or better, give the pot a good shake, afterwards allowing the leaves to settle.

Eighthly, one should drink out of a good breakfast cup — that is, the cylindrical type of cup, not the flat, shallow type. The breakfast cup holds more, and with the other kind one’s tea is always half cold before one has well started on it.

Ninthly, one should pour the cream off the milk before using it for tea. Milk that is too creamy always gives tea a sickly taste.

Tenthly, one should pour tea into the cup first. This is one of the most controversial points of all; indeed in every family in Britain there are probably two schools of thought on the subject. The milk-first school can bring forward some fairly strong arguments, but I maintain that my own argument is unanswerable. This is that, by putting the tea in first and stirring as one pours, one can exactly regulate the amount of milk whereas one is liable to put in too much milk if one does it the other way round.

Lastly, tea — unless one is drinking it in the Russian style — should be drunk without sugar. I know very well that I am in a minority here. But still, how can you call yourself a true tealover if you destroy the flavour of your tea by putting sugar in it? It would be equally reasonable to put in pepper or salt. Tea is meant to be bitter, just as beer is meant to be bitter. If you sweeten it, you are no longer tasting the tea, you are merely tasting the sugar; you could make a very similar drink by dissolving sugar in plain hot water.

Some people would answer that they don’t like tea in itself, that they only drink it in order to be warmed and stimulated, and they need sugar to take the taste away. To those misguided people I would say: Try drinking tea without sugar for, say, a fortnight and it is very unlikely that you will ever want to ruin your tea by sweetening it again.

These are not the only controversial points to arise in connexion with tea drinking, but they are sufficient to show how subtilized the whole business has become. There is also the mysterious social etiquette surrounding the teapot (why is it considered vulgar to drink out of your saucer, for instance?) and much might be written about the subsidiary uses of tealeaves, such as telling fortunes, predicting the arrival of visitors, feeding rabbits, healing burns and sweeping the carpet. It is worth paying attention to such details as warming the pot and using water that is really boiling, so as to make quite sure of wringing out of one’s ration the twenty good, strong cups of that two ounces, properly handled, ought to represent.

(taken from The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume 3, 1943-45, Penguin ISBN, 0-14-00-3153-7)

Amazing Tea Taxonomy 茶叶分类

Making The Perfect Cup Of Tea

Sensible advice for the tea novice

Making the perfect cup of tea doesn’t have to be difficult. There are plenty of ways you can make the perfect cup, depending on where you are and what you’re doing. Unlike coffee, you don’t need a complicated apparatus or freeze-dried instant granules to enjoy your favorite beverage.

Making the perfect cup of tea doesn’t have to be difficult. There are plenty of ways you can make the perfect cup, depending on where you are and what you’re doing. Unlike coffee, you don’t need a complicated apparatus or freeze-dried instant granules to enjoy your favorite beverage.

Regardless of your location when you’re making tea, always choose loose leaf tea over pre-bagged tea. Loose tea leaves are a better quality product that can often (depending on type and brand) be re-brewed for multiple infusions. From formal tea time sipping to tea on the go, you can have the perfect cup anytime.

On the Run

Tea is easier to make on the run than coffee. You just need access to hot water or a microwave. For best results, choose a ceramic travel mug. Most come with silicon sleeves and lids. You can heat water in the microwave if a…

View original post 466 more words

a literary tea party

I’d never come across this parody poem before – thanks, and well blogged!

I found this poem on a rainy day in my high school library, after checking out a thick dusty book title Parodies. (I was such a nerd! The last time someone had checked out the book was in 1972! I bought the book off the librarian when they decided to revamp their collection…)

I found this poem on a rainy day in my high school library, after checking out a thick dusty book title Parodies. (I was such a nerd! The last time someone had checked out the book was in 1972! I bought the book off the librarian when they decided to revamp their collection…)

You may have to brush up on your classic poets to appreciate the wit of this poem – I sure did! I still don’t catch some of the allusions.

I was most familiar with Poe’s commentary, after his poem, The Bells. And of course, Robert Burns‘ whiskey-laced offering just makes sense.

It is just as the title describes: All the poets, sitting down to tea, all start waxing eloquent about the kettle and the cups…

The Poets at Tea

by Barry Pain

Pour, varlet, pour the water,

The water steaming hot!

A spoonful for…

View original post 652 more words

Charleston Tea Plantation

Tea from the Deep South? Who knew?

The book on Kindle – free!

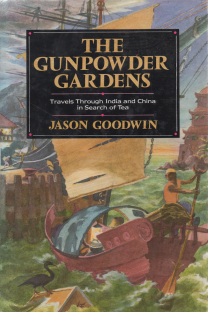

Phew! Just letting everyone (and everyone’s wife, husband, child, neighbour) know that The Gunpowder Gardens: Travels through India and China in Search of Tea is available on Kindle for free this weekend.

The weather looked a bit dodgy, so I thought I’d give the book away instead of doing the garden…

Download it – share it – and if you enjoy it, please don’t forget to leave a review on Amazon…

The Tea Caddy

Here’s a blog post I wrote for http://www.tching.com/2012/07/tactile-tea/ – lovely illustrations on the home site!

Tactile tea

My grandmother kept her tea in a wooden caddy that had an ivory band around the lid, and a tiny brass-bound lock that turned with a smooth and promising click. The lock, I suppose, was an echo of the 18th Century, when tea was a luxury so rare and valuable it needed to be protected from the servants.

Raise the lid, and inside was a childish dream of a box: two compartments with snug and perfectly fitted lids, each lifted by a small, knurled mahogany handle. The lids were almost interchangeable – but not quite. One, I think, was very slightly smaller than the other; and the sides lined up exactly only in one direction, like a child’s toy. The compartments were lined with lead, covered in silver paper, which helped give the caddy its mysterious and alluring weight. Say what you like about lead, but it’s a glorious substance in its own right – blue-grey, malleable, easily melted, easily worked. Some of our plumbing (from plumbum, the latin for lead) was still made of it back then.

The workmanship hinted at secret drawers, like a diplomat’s escritoire – or a Joe 90s’ briefcase – cunningly joinered to be invisible to the uninitiated. It should have contained – what? Gold doubloons, perhaps, or strings of pearls; or a letter on which the fate of empires might depend, onionskin folded and refolded, inscribed by hand in a spidery copperplate.

Inside each compartment was loose-leaf tea, and one small wooden scoop. In the first was Darjeeling, scattered as promised with flecks of gold. The scent was grassy and fresh, but it wasn’t until later that I learned that the grade of leaf was known as TGFOP, Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe. What astonished me even then was that every leaf was furled, like an umbrella, along its length. The second compartment contained Assam, my grandmother’s breakfast tea. The leaf was much smaller, but silkier to the touch.

Both teas had an ineffable color, which I liked. The Darjeeling, with its golden tips and hints of green, was like a bolt of Hebridean tweed, with the grain of a rare wood. The Assam was absolute, uniformly black, but the sort of rich unadulterated black you don’t see much nowadays – letterpress black, the black of colonial pamphlets or Italian engravings. Like the world’s first postage stamp, Queen Victoria’s Penny Black: dusty black, with a bloom all its own.

The texture of tea is something I’ve never quite gotten over, and it’s what I miss most when I resort to the companionable teabag, with its filling of macerated leaf. I love Chinese gunpowder tea, rolled and furled the size of a pinhead, the color of dull jade; the spidery, generous leaves of Lapsang Souchong; or the susurrating fillets of panfried Long Jing, still whole and perfectly – irrationally – flat. These are hand-picked, hand-made, bearing the stamp of human skills and traditions. We live in an age of perfect, digitally controlled precision: everything we need is the calculated product of design, technology, and mass production. So while it’s only millionaires who can afford a Savile Row suit, or a hand-built car, or a pair of tailored brogues – or cigars rolled on the thighs of women in the Caribbean heat! – it’s nice to know that you can still have tea. China or India, anyone?

Turkish tea

In Istanbul the other day, I was talking tea with a tea planter’s daughter who had returned from a trip along Turkey’s dramatic Black Sea coast. She’d visited the tea growing region of Rize, and was gently appalled by the rough and ready methods the pluckers used to harvest the leaf. Using shears! The shears were attached to a bag, so the contraption looked like a pelican’s beak…

And yet…and yet…On a hot day near the Grand Bazaar, nothing in the world could be so refreshing as a tulip-shaped glass of tea, with a little sugar!